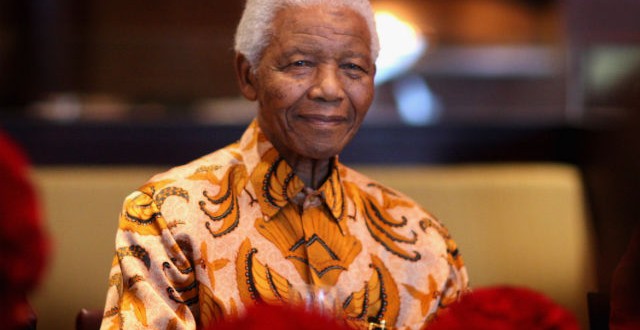

The South African anti-apartheid activist died Thursday at his home after a lengthy illness, said South African President Jacob Zuma.

“He passed peacefully,” said Mr. Zuma in a state address. “This is a moment of our deepest sorrow. Our nation has lost its greatest son.”

Mandela has being treated for the past three months in a Pretoria hospital for a lung infection. The country’s first black president had suffered a series of illnesses after contracting tuberculosis during his nearly 30 years in prison for opposing apartheid.

Mandela was discharged home in “critical but stable” condition. Members of his family acknowledged his increasingly fragile condition.

Mandela was born in the Transkei, a region of rolling green hills near the southern tip of the African continent. In his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, he recalled his childhood as a simple, joyful time. He herded sheep and cows near his mother’s huts and played barefoot with other boys. He was educated by British missionaries, got a law degree and eventually opened the first black law firm in Johannesburg.

In the 1940s, Mandela became active with the Youth League of the African National Congress.

Tapping into the culture of black resistance that was sweeping Johannesburg, Mandela helped organize strikes and demonstrations against the country’s system of racial segregation.

Later, Mandela and other ANC leaders decided that freedom songs and civil disobedience would never topple the apartheid government, so they set up Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC. As a result of Umkhonto we Sizwe’s guerrilla tactics, Mandela and seven other ANC leaders went on trial for sabotage in 1963.

Against the advice of his lawyers, Mandela gave a four-hour closing statement. He used the speech in what’s known as the “Rivonia trial” to attack the apartheid system. Despite facing the death penalty, he defiantly told the court that his actions had been in pursuit of the ideal of a free, democratic society with equal opportunity for people of all races.

“It is an idea for which I hope to live for and to see realized but my Lord, if it needs be, it is an idea for which I am prepared to die,” Mandela said at the time.

Mandela and his codefendants escaped the gallows but were sentenced to life in prison.

He would spend the next 27 years behind bars, much of that time in the maximum security prison on Robben Island. In prison he became a symbol of the anti-apartheid movement and the focal point of international campaigns to do away with racial segregation in South Africa.

‘A War Of Attrition’

One of Mandela’s co-defendants at the Rivonia trial was Ahmed Kathrada, who was one of Mandela’s closest confidants inside and later outside prison.

In an interview with Radio Diaries in 2004, Kathrada recalled Mandela playing a chess game for three days against a young medical student who had recently been incarcerated on the island.

“They played the first day, and when it came to lockup time, the game had not finished because Mandela calculates every move as he does in politics,” Kathrada said.

Mandela persuaded one of the guards to lock the board away in an empty cell. At the end of the next day, the game was still not finished and the guard had to lock it away again.

“In the end, this young chap just gave up. He said, ‘You win. I can’t carry on this way,’ ” Kathrada said. “That’s Mandela; it’s a war of attrition and he won.”

In Mandela’s war of attrition against the apartheid government, South African President F.W. de Klerk made several offers to free him but Mandela would accept only an unconditional release.

In 1990, de Klerk did just that. Apartheid was on its final legs, and Africa’s largest economy was, for the first time in centuries, headed for black majority rule.

‘That Man Saved This Country’

The four years between Mandela’s release from prison and South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994 were tumultuous, however.

Elements within the white apartheid government were desperately trying to retain power. Violent clashes between supporters of the Zulu-based Inkatha Freedom Party and Mandela’s ANC left many foreign observers predicting that South Africa would disintegrate into a bloody civil war.

But Mandela’s paternal, grandfatherly presence had a calming effect across the country. In 1993, he and de Klerk shared the Nobel Peace Prize. After winning the 1994 election, Mandela reached out to South Africans of all races to help build an equitable and prosperous country.

“We place our vision of a new constitutional order for South Africa on the table not as conquerors, prescribing to the conquered,” Mandela said at the time. “We speak as fellow citizens to heal the wounds of the past with the intent of constructing a new order based on justice for all. This is the challenge that faces all South Africans today, and it is one to which I am certain we will all rise.”

Possibly his greatest political move was his decision to serve only one term as president. This was partly because he was 80, but also because he said he wanted to establish a tradition of contested, democratic elections.

During the 2004 presidential elections in which Thabo Mbeki won a second term, South Africans of all races stood in long lines to cast their ballots. Before 1994, none of the black people in those lines would have been allowed to vote. Mlongi Sitcholosa, a black schoolteacher waiting to vote in the township of Soweto, credited one man with changing that: Mandela.

“That man saved this country,” Sitcholosa said. “If it wasn’t because of him this country would have gone to flame, but because of his wisdom and his intelligence he saved this country.”

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day