A new study claimed that the Stone Age people made their tools and weapons independently, instead of an earlier belief that migrating African tribes built them.

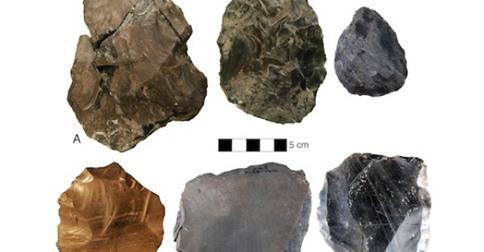

Named after flint tools discovered in the 19th century in the Levallois-Perret suburb of Paris in France, Levallois technique is a distinctive style of flint knapping developed by early humans during the Paleolithic.

This technique involves the multistage shaping of a mass of stone in preparation to detach a flake of predetermined size and shape from a single preferred surface.

Many anthropologists argue that Levallois technique was invented in Africa more than 300,000 years ago and spread to Eurasia with expanding human populations, replacing a more basic type of technology – biface technique – in which a raw block of stone is shaped through the serial removal of interrelated flakes until the remaining volume takes on a desired form, such as a hand axe.

But now a team of archaeologists and anthropologists from the United States and Europe led by Dr Daniel Adler of the University of Connecticut has discovered at the Armenian archaeological site of Nor Geghi that Levallois tools already existed there between 325,000 and 335,000 years ago, suggesting that local populations developed them out of biface technique, which was also found at the site.

The co-existence of the two techniques provides the first clear evidence that local populations developed Levallois technique out of existing biface technique.

“The discovery of thousands of stone artifacts preserved at this unique site provides a major new insight into how Stone Age tools developed during a period of profound human behavioral and biological change”, said Dr Simon Blockley of Royal Holloway, University of London, who is a co-author of the paper describing the discovery in the journal Science.

“The people who lived there 325,000 years ago were much more innovative than previously thought, using a combination of two different technologies to make tools that were extremely important for the mobile hunter-gatherers of the time.”

Moreover, the chemical analysis of several hundred obsidian tools from Nor Geghi shows that early humans at the site utilized obsidian outcrops from as far away as 120 km, suggesting they must have been capable of exploiting large, environmentally diverse territories.

Agencies/Canadajournal

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day