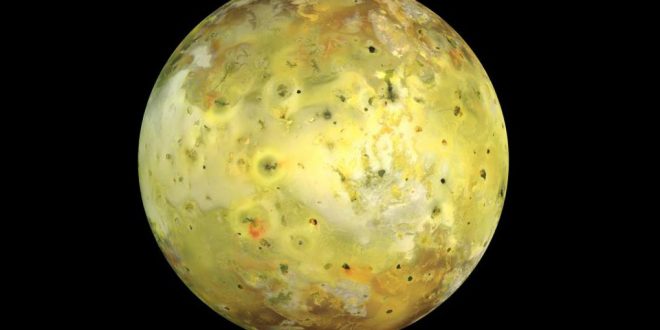

Researchers have detected two massive waves sweeping across the largest lava lake on Jupiter’s moon Io. The lake is called Loki Patera.

lo is the most volcanically active body in the solar system. Infrared images from the Large Binocular Telescope Observatory captured differences in surface temperature on the Jovian moon that suggest that lava waves oscillate through Loki Patera, a large, active volcanic crater stretching 127 miles (200 kilometers) across the moon’s surface.

Swells of lava spreading across the surface of the lake could help explain the periodic changes in brightness seen at Loki Patera, according to a new study describing the observations.

The study considers images taken on March 8, 2015, as Jupiter’s icy moon Europa passed in front of lo. The alignment of the two moons allowed astronomers to isolate heat radiating from volcanoes on lo, as the icy surface of Europa “reflects very little sunlight at infrared wavelengths,” the researchers said in a statement from the University of California, Berkeley.

“This is the first useful map of the entire patera,” study co-author Ashley Davies, an astronomer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in the statement, referring to the crater. “It shows not one, but two resurfacing waves sweeping around the patera. This is much more complex than what was previously thought.”

Using the infrared data, the researchers found a steady increase in surface temperature, from 270 kelvins (26 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 3 degrees Celsius) at the western end of Loki Patera to 330 kelvins (134 degrees F, or 56 degrees C) at the southeastern end. These observations suggest that “the lava had overturned in two waves that each swept from west to east at about a kilometer [3,300 feet] per day,” the researchers said.

Overturn occurs in lava lakes such as Loki Patera because lava on top of the lake cools, thickens and falls into the liquid below, causing a wave of magma to rise up and spread across the surface of the lake. The cycle of hot, incandescent magma rising to the surface and later cooling also explains the periodic brightening and dimming of Loki Patera, the researchers said.

Using information on the temperature and cooling rate of magma on Earth, the researchers determined approximately when the magma rose to the surface of Loki Patera. Their findings suggest that the overturning started at the western end of the lava lake, where the magma was exposed to the surface of the lake between 180 and 230 days before the infrared images were taken. However, magma in the southeastern end appeared to be fresher and hotter, and had been exposed only 75 days before the observations, the researchers said.

“Interestingly, the overturning started at different times on two sides of a cool island in the center of the lake that has been there ever since Voyager photographed it in 1979,” the researchers said in the statement.

“The velocity of overturn is also different on the two sides of the island, which may have something to do with the composition of the magma or the amount of dissolved gas in bubbles in the magma,” study co-author Imke de Pater, an astronomer at UC Berkeley, said in the statement. “There must be differences in the magma supply to the two halves of the patera, and whatever is triggering the start of overturn manages to trigger both halves at nearly the same time but not exactly. These results give us a glimpse into the complex plumbing system under Loki Patera.”

This research was published in Nature.

Agencies/Canadajournal

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day