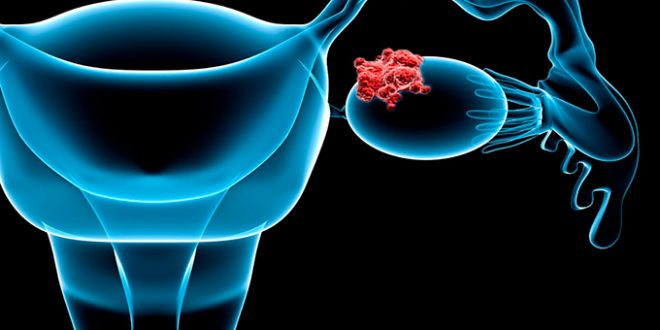

Ovarian cancer begins in the fallopian tubes six-and-a-half years before it turns into the ‘silent killer’, according to a new study from Johns Hopkins suggests.

Some researcherss have suspected that the most common form of ovarian cancer may originate in the fallopian tubes, the thin fibrous tunnels that connect the ovaries to the uterus. The fifth-largest cause of cancer deaths in women, ovarian cancer is generally diagnosed too late in most patients, and fewer than 30 percent of women with the disease survive beyond 10 years.

“Ovarian cancer treatments have not changed much in many decades, and this may be, in part, because we have been studying the wrong tissue of origin for these cancers,” says study leader Victor Velculescu, a professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center. “If studies in larger groups of women confirm our finding that the fallopian tubes are the site of origin of most ovarian cancer, then this could result in a major change in the way we manage this disease for patients at risk.”

For the study, described today in Nature Communications, scientists at the Kimmel Cancer Center and the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston collected tissue samples containing normal cells, ovarian cancers, metastases that had spread elsewhere, and small cancers found in the fallopian tubes. All of the samples came from five women diagnosed with high-grade serous ovarian tumors, the type that accounts for three-quarters of the estimated 22,000 women diagnosed with ovarian cancers each year in the United States. The scientists also collected samples from four women who had undergone the removal of their ovaries and fallopian tubes as a preventative measure against the cancer after finding indicators of being at risk.

The researchers developed a way to isolate the relatively few cancer cells from the larger mass of normal cells and sequenced all of the genes of the samples. The research teams then searched for mistakes in the genetic sequences.

The DNA results showed that all nine patients had lost identical regions of chromosome 17, where the cancer-linked gene p53 is located. This suggests that flaws in the p53 gene is an early step in ovarian cancer development.

All nine patients also had lost portions of chromosomes containing one or both BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which have long been linked to hereditary as well as sporadic breast and ovarian cancers. Four patients had deletions in chromosome 10 where another cancer-linked gene called PTEN is located.

The researchers then worked backwards to determine where the first genetic mutations occurred to cause the cancer, and how long ago those mutations took place. They reasoned that there would likely be fewer mutations in the original cancer cells than in their successors, so they analyzed genetic sequences to create an evolutionary tree. They also used statistical models that accounted for the patient’s age when she was diagnosed with the cancer and the total number of mutations in her cancer to determine the amount of time it took for the cancer to grow.

The researchers concluded that each of the women’s cancers began with genetic mistakes occurring in cells located in the fallopian tubes, and that ovarian cancers developed within an average of 6.5 years among the patients analyzed.

However, the researchers say, when the patients’ cancers reached their ovaries, the progression to metastatic disease occurred rapidly, within an estimated two years on average.

“This aligns with what we see in the clinic, that newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients most often already have widespread disease,” says Velculescu.

Velculescu cautions that medical practice may not change much until additional studies validate their findings, and there are ongoing clinical trials studying the removal of fallopian tubes instead of ovaries in women with cancer-causing hereditary BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Velculescu also notes that the fallopian-first theory may not apply to other, less-common types of ovarian cancer.

Agencies/Canadajournal

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day