Ancient bones of gigantic shark found near Fort Worth, Texas.

Paleontologists at the Sam Noble Museum at the University of Oklahoma are excited about the discovery a 100-million-year-old giant shark that was at least 20 feet long, possibly larger.

The shark remains in question, identified as three vertebrae, were discovered by paleontologist Joseph Frederickson back in 2009. They are described in a study published in the science journal PLOS ONE this past Wednesday, June 3.

Having analyzed the vertebrae and compared them to a description of another such spinal column fragment found in 1997 in Kansas, researcher Joseph Frederickson and his team believe that the fossilized remains all come from the same species.

More precisely, the paleontologists claim that the vertebrae belong to now-extinct mammoth sharks known to the scientific community as Leptostyrax macrorhiza. 100 million years ago, these fish were among the world’s most feared predators.

Writing in the journal PLOS ONE, scientist Joseph Frederickson and fellow researchers explain that, for a long time, Leptostyrax macrorhiza was only known to paleontologists from teeth recovered at sites across North America.

The vertebrae found in Kansas and Texas, however, shed new light on this extinct species in that they make it possible to better estimate just how big these ancient predators could grow to be.

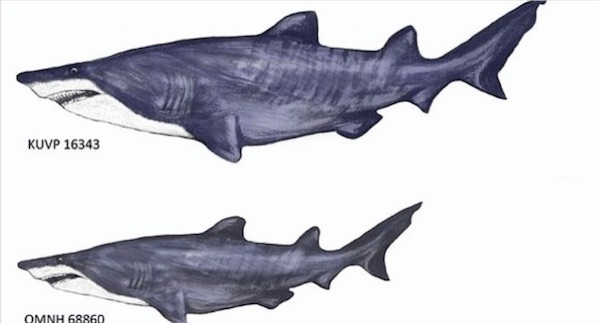

Thus, the spinal column fragment recovered in 1997 from the Kiowa Shale in Kansas likely originates from a shark measuring as much as 32 feet (about 9.8 meters) in length, Live Science details.

As for the three vertebrae discovered in Texas, paleontologists estimate that they were left behind by a Leptostyrax macrorhiza specimen measuring approximately 20 feet (6 meters) from head to tail.

Since no teeth were found anywhere near these spinal column remains, researchers cannot be positive about having correctly identified their species. Still, the discovery of the fossils provides new clues about the biodiversity of ancient North America.

“Neither specimen was recovered with associated teeth, making confident identification of the species impossible,” Joseph Frederickson and his colleagues explain in their PLOS ONE report.

“Regardless of its actual identification, this new specimen provides further evidence that large-bodied lamniform sharks had evolved prior to the Late Cretaceous,” the specialists add.

Agencies/Canadajournal

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day