Researchers have made observations of the smallest asteroid ever described in detail, according to a new report in The Astronomical Journal.

At 6 feet across, the small space stone named 2015 TC25 was also found to be one of the brightest near-Earth asteroids ever discovered. Using information from four different telescopes, a team of scientists reported 2015 TC25 reflects around 60 percent of the sunlight that hits it.

Astronomers at University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory first found TeeCee in October of last year, as its name would suggest, but recently published their findings in The Astronomical Journal after watching the little rock zip through space for a year. Weirdly, TeeCee is extremely bright for an asteroid, despite its small stature. The astronomers estimate the asteroid reflects up to 60 percent of the sunlight that hits it, mostly because it’s made of shiny silicate materials formed in a high-temperature, oxygen-free environment.

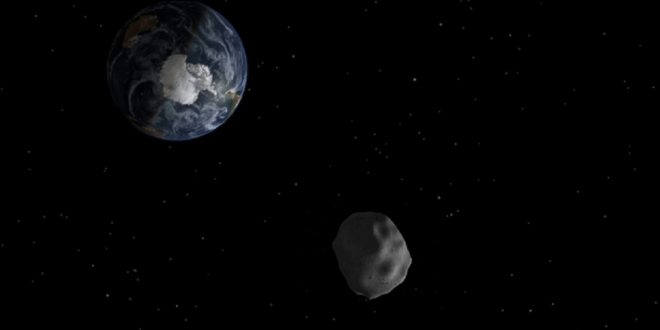

Lead author Vishnu Reddy said that even though TeeCee is a shrimp, it might have bigger implications and could help astronomers learn more about where its bigger asteroid family members are headed. Near-Earth asteroids — ones that break off from the main belt between Mars and Jupiter and pass by Earth — are watched carefully by astronomers just in case one decides to go all Armageddon on us. But Reddy says that’s not really a worry with TeeCee.

“This is the first time we have optical, infrared and radar data on such a small asteroid, which is essentially a meteoroid,” Reddy said. “You can think of it as a meteorite floating in space that hasn’t hit the atmosphere and made it to the ground yet.”

Still, Reddy’s team was interested in the little rock because it was a perfect example of a small-scale meteorite sample untarnished by a traumatic trip through the atmosphere and an impact with earth.

“Being able to observe small asteroids like this one is like looking at samples in space before they hit the atmosphere and make it to the ground,” Reddy said. “It also gives us a first look at their surfaces in pristine condition before they fall through the atmosphere.”

Agencies/Canadajournal

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day