The Cassini probe is set to make its deepest-ever dive through a plume of ice that Saturn’s Enceladus moon sprays into space. It is hoped that the flyby will give NASA new clues about what goes on in the ocean on the moon’s surface and whether it can support life.

During the flyby, which is expected to take place at 3:22pm GMT, Cassini’s ion neutral mass spectrometer (INMS) will attempt to detect molecular hydrogen in the icy water spray.

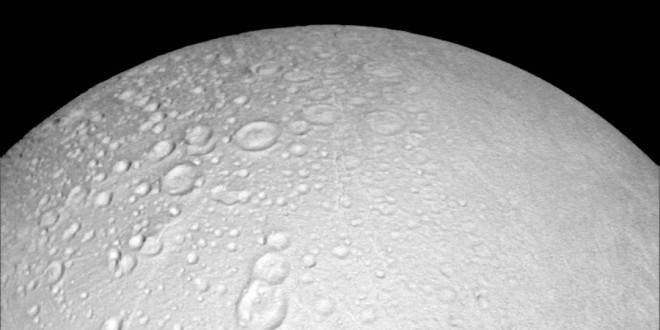

Researchers hope the data will give them better understanding of hydrothermal activity taking place inside the 310-miles-in-diameter Enceladus, which might help answer the question about the likelihood of existence of primitive life forms on the ice-covered moon.

“Confirmation of molecular hydrogen in the plume would be an independent line of evidence that hydrothermal activity is taking place in the Enceladus ocean, on the seafloor,” said Hunter Waite, INMS team lead at Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “The amount of hydrogen would reveal how much hydrothermal activity is going on.”

The Wednesday flyby is not the closest Cassini has ever gotten to the surface of Enceladus but it has never flown at such a low altitude through the geyser. The altitude will enable the probe to detect some heavier molecules including the organic ones.

The spacecraft will also acquire the highest ever resolution images of Enceladus’s south pole during the flyby, Nasa said. The terrain will be illuminated by light reflected from Saturn and advanced processing will be used to remove blurring caused by the spacecraft’s movement during exposure.

The researchers said it will take them months to analyse the data not only from the INMS but also from Cassini’s cosmic dust analyser that is capable of sampling up to 10,000 particles per second.

“Cassini truly has been a discovery machine for more than a decade,” said Curt Niebur, Cassini program scientist at Nasa Headquarters in Washington. “This incredible plunge through the Enceladus plume is an amazing opportunity for Nasa and its international partners on the Cassini mission to ask, ‘Can an icy ocean world host the ingredients for life?'”

The final of Cassini’s close flybys of this icy moon, targeted at an altitude of 3,106 miles will take place on 19 December and will examine how much heat is coming from the moon’s interior.

Cassini, launched in 1997, still has two years to go before it crashes into Saturn’s atmosphere in September 2017.

Agencies/Canadajournal

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day