According to genetic analysis, Newfoundland, the northeastern Canadian island, was populated by three distinct groups — in three different waves — over the last 10,000 years.

When researchers analyzed the DNA of two known cultural groups, the Maritime Archaic and Beothuk, they found the groups brought unique matrilines to the island.

The findings are published in Current Biology on October 12.

“Our paper suggests, based purely on mitochondrial DNA, that the Maritime Archaic were not the direct ancestors of the Beothuk and that the two groups did not share a very recent common ancestor,” says Ana Duggan of McMaster University. “This in turn implies that the island of Newfoundland was populated multiple times by distinct groups.”

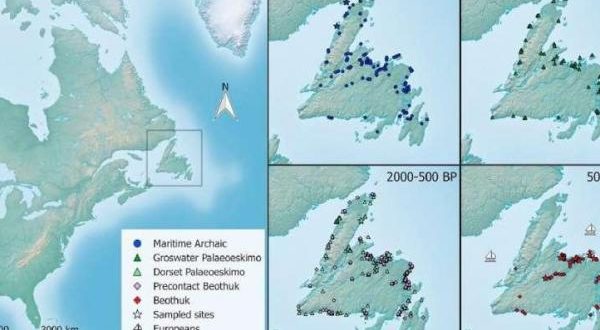

The relationship between the older Maritime Archaic population and Beothuk hadn’t been clear from the archaeological record. With permission from the current-day indigenous community, Duggan and her colleagues, led by Hendrik Poinar, examined the mitochondrial genome diversity of 74 ancient remains from the island together with the archaeological record and dietary isotope profiles. All samples were collected from tiny amounts of bone or teeth.

The sample set included a Maritime Archaic subadult more than 7,700 years old found in the L’Anse Amour burial mound, the oldest known burial mound in North America and one of the first manifestations of the Maritime Archaic tradition. The majority of the Beothuk samples came from the Notre Dame Bay area, where the Beothuk retreated in response to European expansions. Most of those samples are from people that lived on the island within the last 300 years. The DNA evidence showed that the two groups didn’t share a common maternal ancestor in the recent past, but rather one that coalesces sometime in the more distant past.

“These data clearly suggest that the Maritime Archaic people are not the direct maternal ancestors of the Beothuk and thus that the population history of the island involves multiple independent arrivals by indigenous peoples followed by habitation for many generations,” the researchers write. “This shows the extremely rich population dynamics of early peoples on the furthest northeastern edge of the continent.”

Agencies/Canadajournal

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day