It took every inch of the Large Hadron Collider’s 17-mile length to accelerate particles to energies high enough to discover the Higgs boson. Now, imagine an accelerator that could do the same thing in, say, the length of a football field. Or less.

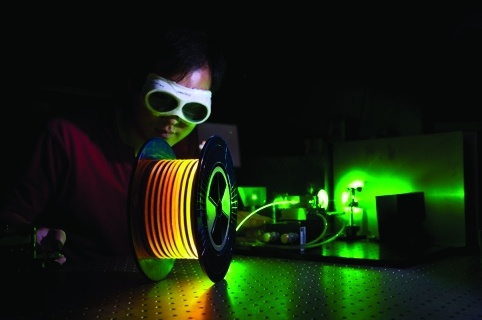

That is the promise of laser-plasma accelerators, which use lasers instead of high-power radio-frequency waves to energize electrons in very short distances. Scientists have grappled with building these devices for two decades, and a new theoretical study predicts that this may be easier than previously thought.

The present limitation of laser induced particle acceleration will be overcome by using multiple lasers at the same time. The coordination of the laser pulses will likely produce electron speeds similar to large-scale particle accelerators.

Lasers that can produce repetitive pulses cannot recharge fast enough to continue to move at such a speed. The opportunities that laser accelerated electrons would provide would be 1,000 times greater than present accelerator technology.

“The effect is like the wake of a boat speeding down a lake. If the wake was big enough, a surfer could ride it,” Leemans, who heads the BELLA Center, explained. “Imagine that the plasma is the lake and the laser is the motorboat. When the laser plows through the plasma, the pressure created by its photons pushes the electrons out of the way. They wind up surfing the wake, or Wakefield, created by the laser as it moves down the accelerator,” he said.

The reduction in size will be estimated by a comparison of CERN’s 17 mile accelerator with the BELLA laser that is about 33 feet square.

The fast moving electrons leave heavy ions behind. As they separate, they release giant electric fields that are at 100 times to 1,000 times bigger than conventional accelerators.

The new accelerators will give physicists the opportunity to find new options for learning how the Earth was created.

Agencies/Canadajournal

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day