A 6,000-year-old burial site revealed that the ritual of burying community and family members near one another dates back to the Neolithic period, according to a new study. Researchers were able to develop a comprehensive picture of ancient burial traditions in Northern Spain.

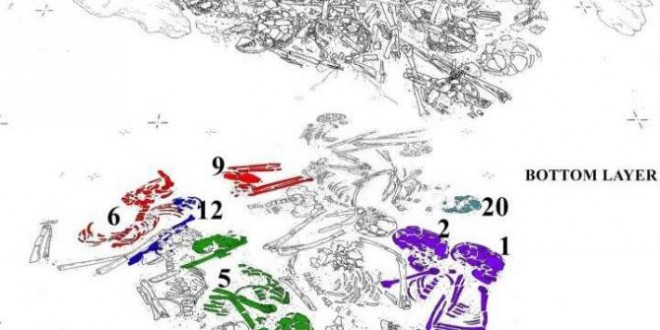

The collective graves of the Neolithic period were made mostly of stone and were large enough to hold many bodies in a communal space. The megalithic tomb in Alto de Reinoso, Burgos differs from this in only one respect: the burial chamber had originally been made from wood over which a stone mound was erected afterwards. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the tomb was used by a community living between 3700 and 3600 AD and spanning about three to four generations. At least 47 bodies have been found. “While the lower layer has been relatively well preserved, numerous disturbances have been observed in the upper layers such as missing skulls, which could be due to a certain kind of ancestral worship,” says Prof. Manuel Rojo Guerra, from the University of Valladolid, Spain.

Way of life revealed

In order to examine the Neolithic community’s way of life, researchers used modern methods to collect individual data such as age, sex, body height, disease, stress markers and signs of violence. This data was also supplemented by information about diet, area of origin, mobility and familial relationships. “This is the first study that presents a detailed picture of how Neolithic people were connected in life and death,” says lead author Prof. Kurt W. Alt, visiting professor at the University of Basel.

Almost half of the deceased were adults; the other half were children and adolescents. The average body height was 159 cm ± 2 cm for men and 150 cm ± 2 cm for women. The adults showed skeletal stress markers and various stages of degenerative diseases of the spine and joints, healed fractures, head injuries and dental diseases such as caries.

Uniform community

Molecular genetic studies also revealed the relationships between individuals in the group, especially on the maternal side. Furthermore, there is evidence that bodies buried close to each other were in some cases also closely related genetically. Apart from three individuals, all of the deceased grew up in the area around the collective grave. A reconstruction of the diet further demonstrates the homogeneous structure of the farming community: the staple food for everyone was cereals (wheat and barley) and animal proteins (sheep, goat and pig in particular).

Agencies/Canadajournal

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day