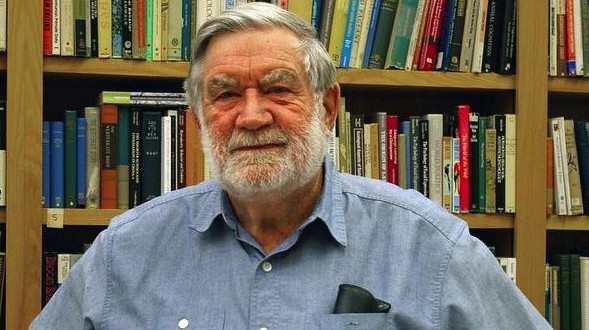

Dr. Peter Marler, a distinguished UC Davis animal behaviorist whose pioneering research into the trills and whistles of birds influenced modern scientific understanding of learning and communication skills in animals, has died at 86.

The cause was pneumonia, said his wife, Judith. He died July 5 while his family was evacuated from his Winters home because of the nearby Monticello wildfire.

Dr. Marler, who made his most enduring contributions in the field of birdsong, wrote more than 100 papers during a long career that began at Cambridge University, where he received his doctorate in zoology in 1954, and that took him around the world doing research while teaching at a number of U.S. universities. He led animal behaviour research at the University of California, Davis, from 1989 to 1994 and was an emeritus professor there.

Two new technologies were central to his field research: the portable tape recorder and the sonic spectrograph, developed in the Second World War to trace the sound of ships’ propellers. Using both, he was one of the first to produce graphic snapshots of birdsong – streaks of ink on paper showing the wave frequency, modulation and pitch of various calls and songs.

From that data, Dr. Marler and his colleagues discovered that some species had repertoires of only a few songs while others had as many as 100. They found they could analyze and differentiate calls within the same species – calls for roosting, seeking food, mating, territory-marking, warning of danger and summoning help, known as mobbing, to ward off an intruder.

In a seminal 1987 paper, co-written with James Gould, he proposed that the drive to learn new things was an adaptive trait – and that animals and humans both had it in their genes. It was a conjecture at the time but genetic biologists later proved him largely correct.

In the early 1960s, he went to Uganda in hopes of detecting language-learning patterns in primates. Although he found that vervets, the long-tailed monkeys he studied for months on end, did not learn calls from their elders, they did communicate. His spectrographic records showed they made specific noises when a leopard was nearby and different sounds when threatened by an eagle. He cited that as proof of monkeys’ ability to transmit knowledge to other members of the species in a distinct way – and suggested that such calls were almost certainly ancestors of human speech.

Peter Robert Marler was born Feb. 24, 1928, in Slough, England, to Gertrude and Robert Marler, a tool maker. At age eight, he befriended a rook and was a devoted bird watcher from then on, said his wife, Judith Marler. Besides his wife, he leaves three children, Christopher, Catherine and Marianne.

Agencies/Canadajournal

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day

Canada Journal – News of the World Articles and videos to bring you the biggest Canadian news stories from across the country every day